Bruger:Pugilist/Sandkasse/Demokraternes historie

The Democratic Party of the United States is the oldest voter-based political party in the world, tracing its heritage back to the anti-Federalists of the 1790s.[1][2][3] During the "Second Party System", from 1832 to the mid-1850s, under presidents Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren, James K. Polk, the Democrats usually bested the opposition Whig Party by narrow margins. Both parties worked hard to build grassroots organizations and maximize the turnout of voters, which often reached 80 percent or 90 percent. Both parties used patronage extensively to finance their operations, which included emerging big city political machines as well as national networks of newspapers. The Democratic party was a proponent for farmers across the country, urban workers, and new immigrants. It was especially attractive to Irish immigrants who increasingly controlled the party machinery in the cities. The party was much less attractive to businessmen, plantation owners, Evangelical Protestants, and social reformers. The party advocated westward expansion, Manifest Destiny, greater equality among all white men, and opposition to the national banks. In 1860 the Civil War began between the mostly-Republican North against the mostly-Democratic, slaveholding South.

From 1860 to 1932, in the era of the Civil War to the Great Depression, the opposing Republican Party, organized in the mid-1850s from the ruins of the Whig Party and some other smaller splinter groups, was dominant in presidential politics. The Democrats elected only two presidents to four terms of office for 72 years: Grover Cleveland (in 1884 and 1892) and Woodrow Wilson (in 1912 and 1916). Over the same period, the Democrats proved more competitive with the Republicans in Congressional politics, enjoying House of Representatives majorities (as in the 65th Congress) in 15 of the 36 Congresses elected, although only in five of these did they form the majority in the United States Senate. The Party was split between the "Bourbon Democrats", representing Eastern business interests, and the agrarian elements comprising poor farmers in the South and West. The agrarian element, marching behind the slogan of "free silver" (i.e. in favor of inflation), captured the Party in 1896, and nominated the "Great Commoner", William Jennings Bryan in 1896, 1900 and 1908; he lost every time. Both Bryan and Wilson were leaders of the "Progressive Movement", 1890s–1920s.

Starting with 32nd President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932 during the Great Depression, the Party dominated the "Fifth Party System", with its liberal/progressive policies and programs with the "New Deal" coalition to combat the emergency bank closings and the continuing financial depression since the famous "Wall Street Crash of 1929" and later going into the crises leading up to the Second World War of 1939/1941 to 1945. The Democrats and the Democratic Party, finally lost the White House and control of the executive branch of government only after Roosevelt's death in April 1945 near the end of the War, and after the continuing post-war administration of Roosevelt's third Vice President of the United States, Harry S Truman, former Senator from Missouri, (for 1945 to 1952, elections of 1944 and the "stunner" of 1948). A new Republican Party president was only elected later in the following decade of the early 1950s with the losses by two-time nominee, the Governor of Illinois, Adlai Stevenson (grandson of the former Vice President with the same name of the 1890s) to the very popular war hero and commanding general in World War II, General Dwight D. Eisenhower (in 1952 and 1956).

With two brief interruptions since the "Great Depression", and World War II eras, the Democrats with unusually large majorities for over four decades, controlled the lower house of the United States Congress in the House of Representatives from 1930 until 1994, and the U.S. Senate for most of that same period, electing the Speaker of the House and the Representatives' majority leaders/committee chairs along with the upper house of the Senate's majority leaders and committee chairmen. Important Democratic progressive/liberal leaders included Presidents: 33rd – Harry S Truman, [of Missouri], (1945–1953), and 36th – Lyndon B. Johnson, [of Texas], (1963–1969), as well as the earlier Kennedy brothers of 35th President John F. Kennedy, [of Massachusetts], (1961–1963), Senators Robert F. Kennedy, of New York, and Senator Edward M. ("Teddy") Kennedy, of Massachusetts who carried the flag for modern American political liberalism. Since the Presidential Election of 1976, Democrats have won five out of the last ten presidential elections, winning in the presidential elections of 1976 (with 39th President Jimmy Carter of Georgia, 1976–1981), 1992 and 1996 (with 42nd President Bill Clinton of Arkansas, 1993–2001), and 2008 and 2012 (with 44th President Barack Obama of Illinois, 2009–2017).

Social scientists Theodore Caplow et al. argue, "the Democratic party, nationally, moved from left-center toward the center in the 1940s and 1950s, then moved further toward the right-center in the 1970s and 1980s."[4]

Presidency of John Quincy Adams (1828 – 1829) redigér

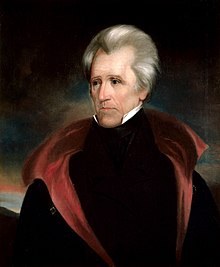

The modern Democratic Party emerged in the 1830s from former factions of the Democratic-Republican Party, which had largely collapsed by 1824. It was built by Martin Van Buren who assembled a cadre of politicians in every state behind war hero Andrew Jackson of Tennessee .[5]

Presidency of Andrew Jackson (1828 – 1837) redigér

Jacksonian Democracy redigér

The spirit of Jacksonian Democracy animated the party from the early 1830s to the 1850s, shaping the Second Party System, with the Whig Party the main opposition. After the disappearance of the Federalists after 1815, and the Era of Good Feelings (1816–24), there was a hiatus of weakly organized personal factions until about 1828–32, when the modern Democratic Party emerged along with its rival the Whigs. The new Democratic Party became a coalition of farmers, city-dwelling laborers, and Irish Catholics.[6]

Behind the party platforms, acceptance speeches of candidates, editorials, pamphlets and stump speeches, there was a widespread consensus of political values among Democrats. As Norton explains:

The Democrats represented a wide range of views but shared a fundamental commitment to the Jeffersonian concept of an agrarian society. They viewed the central government as the enemy of individual liberty. The 1824 "corrupt bargain" had strengthened their suspicion of Washington politics. ... Jacksonians feared the concentration of economic and political power. They believed that government intervention in the economy benefited special-interest groups and created corporate monopolies that favored the rich. They sought to restore the independence of the individual—the artisan and the ordinary farmer—by ending federal support of banks and corporations and restricting the use of paper currency, which they distrusted. Their definition of the proper role of government tended to be negative, and Jackson's political power was largely expressed in negative acts. He exercised the veto more than all previous presidents combined. Jackson and his supporters also opposed reform as a movement. Reformers eager to turn their programs into legislation called for a more active government. But Democrats tended to oppose programs like educational reform mid the establishment of a public education system. They believed, for instance, that public schools restricted individual liberty by interfering with parental responsibility and undermined freedom of religion by replacing church schools. Nor did Jackson share reformers' humanitarian concerns. He had no sympathy for American Indians, initiating the removal of the Cherokees along the Trail of Tears.[7]

The Party was weakest in New England, but strong everywhere else and won most national elections thanks to strength in New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia (by far, the most populous states at the time), and the American frontier. Democrats opposed elites and aristocrats, the Bank of the United States, and the whiggish modernizing programs that would build up industry at the expense of the yeoman or independent small farmer.[8]

Historian Frank Towers has specified an important ideological divide:

Democrats stood for the 'sovereignty of the people' as expressed in popular demonstrations, constitutional conventions, and majority rule as a general principle of governing, whereas Whigs advocated the rule of law, written and unchanging constitutions, and protections for minority interests against majority tyranny.[9]

From 1828 to 1848, banking and tariffs were the central domestic policy issues. Democrats strongly favored, and Whigs opposed, expansion to new farm lands, as typified by their expulsion of eastern American Indians and acquisition of vast amounts of new land in the West after 1846. The party favored the War with Mexico and opposed anti-immigrant nativism. Both Democrats and Whigs were divided on the issue of slavery. In the 1830s, the Locofocos in New York City were radically democratic, anti-monopoly, and were proponents of hard money and free trade.[10][11] Their chief spokesman was William Leggett. At this time labor unions were few; some were loosely affiliated with the party.[12]

Presidency of Martin Van Buren (1837 – 1841) redigér

Presidency of John Tyler (1841 – 1845) redigér

Foreign policy was a major issue in the 1840s; War threatened with Mexico over Texas, and with Britain over Oregon. Democrats strongly supported Manifest Destiny and most Whigs strongly opposed it. The 1844 election was a showdown, with the Democrat James K. Polk narrowly defeating Whig Henry Clay on the Texas issue.[13]

John Mack Faragher's analysis of the political polarization between the parties is that:

Most Democrats were wholehearted supporters of expansion, whereas many Whigs (especially in the North) were opposed. Whigs welcomed most of the changes wrought by industrialization but advocated strong government policies that would guide growth and development within the country's existing boundaries; they feared (correctly) that expansion raised a contentious issue the extension of slavery to the territories. On the other hand, many Democrats feared industrialization the Whigs welcomed. ... For many Democrats, the answer to the nation's social ills was to continue to follow Thomas Jefferson's vision of establishing agriculture in the new territories in order to counterbalance industrialization.[14]

Presidency of James K. Polk (1845 – 1849) redigér

Presidency of Zachary Taylor (1849 – 1850) redigér

Presidency of Millard Fillmore (1850 – 1853) redigér

The Democratic National Committee (DNC) was created in 1848 at the convention that nominated General Lewis Cass, who lost to General Zachary Taylor of the Whigs. A major cause of the defeat was that the new Free Soil Party, which opposed slavery expansion, split the Democratic Party, particularly in New York, where the electoral votes went to Taylor. Democrats in Congress passed the Compromise of 1850 designed to put the slavery issue to rest while resolves issued involving territories gained following the War with Mexico.. In state after state, however, the Democrats gained small but permanent advantages over the Whig Party, which finally collapsed in 1852, fatally weakened by division on slavery and nativism. The fragmented opposition could not stop the election of Democrats Franklin Pierce in 1852 and James Buchanan in 1856.[15]

Presidency of Franklin Pierce (1853 – 1857) redigér

Presidency of James Buchanan (1857 – 1861) redigér

During 1858–60, Senator Stephen A. Douglas confronted President Buchanan in a furious battle for control of the party. Douglas finally won, but his nomination signaled defeat for the Southern wing of the party, and it walked out of the 1860 convention and nominated its own presidential ticket.[16]

Young America redigér

Yonatan Eyal (2007) argues that the 1840s and 1850s were the heyday of a new faction of young Democrats called "Young America". Led by Stephen A. Douglas, James K. Polk, Franklin Pierce, and New York financier August Belmont, this faction explains, broke with the agrarian and strict constructionist orthodoxies of the past and embraced commerce, technology, regulation, reform, and internationalism. The movement attracted a circle of outstanding writers, including William Cullen Bryant, George Bancroft, Herman Melville and Nathaniel Hawthorne. They sought independence from European standards of high culture and wanted to demonstrate the excellence and exceptionalism of America's own literary tradition.[17]

In economic policy Young America saw the necessity of a modern infrastructure with railroads, canals, telegraphs, turnpikes, and harbors; they endorsed the "market revolution" and promoted capitalism. They called for Congressional land grants to the states, which allowed Democrats to claim that internal improvements were locally rather than federally sponsored. Young America claimed that modernization would perpetuate the agrarian vision of Jeffersonian Democracy by allowing yeomen farmers to sell their products and therefore to prosper. They tied internal improvements to free trade, while accepted moderate tariffs as a necessary source of government revenue. They supported the Independent Treasury (the Jacksonian alternative to the Second Bank of the United States) not as a scheme to quash the special privilege of the Whiggish monied elite, but as a device to spread prosperity to all Americans.[18]

Breakdown of the Second Party System, 1854–1859 redigér

Sectional confrontations escalated during the 1850s, the Democratic Party split between North and South grew deeper. The conflict was papered over at the 1852 and 1856 conventions by selecting men who had little involvement in sectionalism, but they made matters worse. Historian Roy F. Nichols explains why Franklin Pierce was not up to the challenges a Democratic president had to face:

- As a national political leader Pierce was an accident. He was honest and tenacious of his views but, as he made up his mind with difficulty and often reversed himself before making a final decision, he gave a general impression of instability. Kind, courteous, generous, he attracted many individuals, but his attempts to satisfy all factions failed and made him many enemies. In carrying out his principles of strict construction he was most in accord with Southerners, who generally had the letter of the law on their side. He failed utterly to realize the depth and the sincerity of Northern feeling against the South and was bewildered at the general flouting of the law and the Constitution, as he described it, by the people of his own New England. At no time did he catch the popular imagination. His inability to cope with the difficult problems that arose early in his administration caused him to lose the respect of great numbers, especially in the North, and his few successes failed to restore public confidence. He was an inexperienced man, suddenly called to assume a tremendous responsibility, who honestly tried to do his best without adequate training or temperamental fitness.[19]

In 1854, over vehement opposition, the main Democratic leader in the Senate, Stephen Douglas of Illinois, pushed through the Kansas–Nebraska Act. It established that settlers in Kansas Territory could vote to decide to allow or not allow slavery. Thousands of men moved in from North and South with the goal of voting slavery down or up, and their violence shook the nation. A major re-alignment took place among voters and politicians, with new issues, new parties, and new leaders. The Whig Party dissolved entirely.[20]

North and South pull apart redigér

The crisis for the Democratic Party came in the late 1850s, as northern Democrats increasingly rejected national policies demanded by the southern Democrats. The demands were to support slavery outside the South. Southerners insisted that full equality for their region required the government to acknowledge the legitimacy of slavery outside the South. The southern demands included a fugitive slave law to recapture runaway slaves; opening Kansas to slavery; forcing a pro-slavery constitution on Kansas; acquire Cuba (where slavery already existed); accepting the Dred Scott decision of the Supreme Court; and adopting a federal slave code to protect slavery in the territories. President Buchanan went along with these demands; Douglas refused. Douglas proved a much better politician than Buchanan, but the bitter battle lasted for years and permanently alienated the northern and southern wings.[21]

When the new Republican Party formed in 1854 on the basis of refusing to tolerate the expansion of slavery into the territories, many northern Democrats (especially Free Soilers from 1848) joined it. The Republicans in 1854 now had a majority in most, but not all of the northern states. It had practically no support south of the Mason–Dixon line. The formation of the new short-lived Know-Nothing Party allowed the Democrats to win the presidential election of 1856.[20] Buchanan, a Northern "Doughface" (his base of support was in the pro-slavery South), split the party on the issue of slavery in Kansas when he attempted to pass a Federal slave code as demanded by the South; most Democrats in the North rallied to Senator Douglas, who preached "Popular Sovereignty" and believed that a Federal slave code would be undemocratic.[22]

The Democratic Party was unable to compete with the Republican Party, which controlled nearly all northern states by 1860, bringing a solid majority in the Electoral College. The Republicans claimed that the northern Democrats, including Doughfaces such as Pierce and Buchanan, and advocates of popular sovereignty such as Stephen A. Douglas and Lewis Cass, were all accomplices to Slave Power. The Republicans argued that slaveholders, all of them Democrats, had seized control of the federal government and were blocking the progress of liberty.[23]

In 1860 the Democrats were unable to stop the election of Republican Abraham Lincoln, even as they feared his election would lead to civil war. The Democrats split over the choice of a successor to President Buchanan along Northern and Southern lines; factions of the party provided two separate candidacies for President in the election of 1860, in which the Republican Party gained ascendancy.[24]

Some Southern Democratic delegates followed the lead of the Fire-Eaters by walking out of the Democratic convention at Charleston's Institute Hall in April 1860 and were later joined by those who, once again led by the Fire-Eaters, left the Baltimore Convention the following June when the convention rejected a resolution supporting extending slavery into territories whose voters did not want it. The Southern Democrats nominated the pro-slavery incumbent Vice-President, John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky, for President and General Joseph Lane, former governor of Oregon, for Vice President.[25]

The Northern Democrats proceeded to nominate Douglas of Illinois for President and former Governor of Georgia Herschel Vespasian Johnson for Vice-President, while some southern Democrats joined the Constitutional Union Party, backing its nominees (who had both been prominent Whig leaders), former Senator John Bell of Tennessee for President and the politician Edward Everett of Massachusetts for Vice-President. This fracturing of the Democrats left them powerless. Republican Abraham Lincoln was elected the 16th President of the United States. Douglas campaigned across the country calling for unity and came in second in the popular vote, but carried only Missouri and New Jersey. Breckinridge carried 11 slave states, coming in second in the Electoral vote, but third in the popular vote.[26]

Presidency of Abraham Lincoln (1861 – 1865) redigér

Civil War redigér

During the Civil War, Northern Democrats divided into two factions, the War Democrats, who supported the military policies of President Lincoln, and the Copperheads, who strongly opposed them. No party politics were allowed in the Confederacy, whose political leadership, mindful of the welter prevalent in antebellum American politics and with a pressing need for unity, largely viewed political parties as inimical to good governance and as being especially unwise in wartime. Consequently, the Democratic Party halted all operations during the life of the Confederacy, 1861-65.[27]

Partisanship flourished in the North and strengthened the Lincoln Administration as Republicans automatically rallied behind it. After the attack on Fort Sumter, Douglas rallied northern Democrats behind the Union, but when Douglas died, the party lacked an outstanding figure in the North, and by 1862 an anti-war peace element was gaining strength. The most intense anti-war elements were the Copperheads.[27] The Democratic Party did well in the 1862 congressional elections, but in 1864 it nominated General George McClellan, a War Democrat, on a peace platform, and lost badly because many War Democrats bolted to National Union candidate Abraham Lincoln. Many former Democrats became Republicans, especially soldiers such as generals Ulysses S. Grant and John A. Logan.[28]

Presidency of Andrew Johnson (1865 – 1869) redigér

In the 1866 elections, the Radical Republicans won two-thirds majorities in Congress and took control of national affairs. The large Republican majorities made Congressional Democrats helpless, though they unanimously opposed the Radicals' Reconstruction policies.[29] Realizing that the old issues were holding it back, the Democrats tried a "New Departure" that downplayed the War and stressed such issues as corruption and white supremacy.

Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant (1869 – 1877) redigér

Regardless, war hero Ulysses S. Grant led the Republicans to landslides in 1868 and 1872.[30]

Presidency of Rutherford B. Hayes (1877 – 1881) redigér

Presidency of James A. Garfield (1881 – 1881) redigér

Presidency of Chester A. Arthur (1881 – 1885) redigér

The Democrats lost consecutive presidential elections from 1860 through 1880 (1876 was in dispute) and did not win the presidency until 1884. The party was weakened by its record of opposition to the war but nevertheless benefited from White Southerners' resentment of Reconstruction and consequent hostility to the Republican Party. The nationwide depression of 1873 allowed the Democrats to retake control of the House in the 1874 Democratic landslide.[kilde mangler]

The Redeemers gave the Democrats control of every Southern state (by the Compromise of 1877); the disenfranchisement of blacks took place 1880–1900. From 1880 to 1960 the "Solid South" voted Democratic in presidential elections (except 1928). After 1900, a victory in a Democratic primary was "tantamount to election" because the Republican Party was so weak in the South.[kilde mangler]

Presidency of Grover Cleveland (1885 – 1889) redigér

Although Republicans continued to control the White House until 1884, the Democrats remained competitive, especially in the mid-Atlantic and lower Midwest, and controlled the House of Representatives for most of that period. In the election of 1884, Grover Cleveland, the reforming Democratic Governor of New York, won the Presidency, a feat he repeated in 1892, having lost in the election of 1888.[kilde mangler]

Cleveland was the leader of the Bourbon Democrats. They represented business interests, supported banking and railroad goals, promoted laissez-faire capitalism, opposed imperialism and U.S. overseas expansion, opposed the annexation of Hawaii, fought for the gold standard, and opposed Bimetallism. They strongly supported reform movements such as Civil Service Reform and opposed corruption of city bosses, leading the fight against the Tweed Ring.[kilde mangler]

The leading Bourbons included Samuel J. Tilden, David Bennett Hill and William C. Whitney of New York, Arthur Pue Gorman of Maryland, Thomas F. Bayard of Delaware, Henry M. Mathews and William L. Wilson of West Virginia, John Griffin Carlisle of Kentucky, William F. Vilas of Wisconsin, J. Sterling Morton of Nebraska, John M. Palmer of Illinois, Horace Boies of Iowa, Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar of Mississippi, and railroad builder James J. Hill of Minnesota. A prominent intellectual was Woodrow Wilson.[31]

Presidency of Benjamin Harrison (1889 – 1893) redigér

Presidency of Grover Cleveland (1893 – 1897) redigér

The Bourbons were in power when the Panic of 1893 hit, and they took the blame. A fierce struggle inside the party ensued, with catastrophic losses for both the Bourbon and agrarian factions in 1894, leading to the showdown in 1896. Just before the 1894 election, President Cleveland was warned by an advisor:

- "We are on the eve of very dark night, unless a return of commercial prosperity relieves popular discontent with what they believe Democratic incompetence to make laws, and consequently with Democratic Administrations anywhere and everywhere."[32]

The warning was appropriate, for the Republicans won their biggest landslide in decades, taking full control of the House, while the Populists lost most of their support. However, Cleveland's factional enemies gained control of the Democratic Party in state after state, including full control in Illinois and Michigan, and made major gains in Ohio, Indiana, Iowa and other states. Wisconsin and Massachusetts were two of the few states that remained under the control of Cleveland's allies. The opposition Democrats were close to controlling two thirds of the vote at the 1896 national convention, which they needed to nominate their own candidate. However they were not united and had no national leader, as Illinois governor John Peter Altgeld had been born in Germany and was ineligible to be nominated for president.[33]

Presidency of William McKinley (1897 – 1901) redigér

Religious divisions were sharply drawn.[34] Methodists, Congregationalists, Presbyterians, Scandinavian Lutherans and other pietists in the North were closely linked to the Republican Party. In sharp contrast, liturgical groups, especially the Catholics, Episcopalians, and German Lutherans, looked to the Democratic Party for protection from pietistic moralism, especially prohibition. Both parties cut across the class structure, with the Democrats gaining more support from the lower classes and Republicans more support from the upper classes.[kilde mangler]

Cultural issues, especially prohibition and foreign language schools, became matters of contention because of the sharp religious divisions in the electorate. In the North, about 50 percent of voters were pietistic Protestants (Methodists, Scandinavian Lutherans, Presbyterians, Congregationalists, Disciples of Christ) who believed the government should be used to reduce social sins, such as drinking.[34]

Liturgical churches (Roman Catholics, German Lutherans, Episcopalians) comprised over a quarter of the vote and wanted the government to stay out of the morality business. Prohibition debates and referendums heated up politics in most states over a period of decade, as national prohibition was finally passed in 1918 (and repealed in 1932), serving as a major issue between the wet Democrats and the dry Republicans.[34]

The Free Silver Movement redigér

Grover Cleveland led the party faction of conservative, pro-business Bourbon Democrats, but as the depression of 1893 deepened, his enemies multiplied. At the 1896 convention the silverite-agrarian faction repudiated the president, and nominated the crusading orator William Jennings Bryan on a platform of free coinage of silver. The idea was that minting silver coins would flood the economy with cash and end the depression. Cleveland supporters formed the National Democratic Party (Gold Democrats), which attracted politicians and intellectuals (including Woodrow Wilson and Frederick Jackson Turner) who refused to vote Republican.[35]

Bryan, an overnight sensation because of his "Cross of Gold" speech, waged a new-style crusade against the supporters of the gold standard. Criss-crossing the Midwest and East by special train — he was the first candidate since 1860 to go on the road — he gave over 500 speeches to audiences in the millions. In St. Louis he gave 36 speeches to workingmen's audiences across the city, all in one day. Most Democratic newspapers were hostile toward Bryan, but he seized control of the media by making the news every day, as he hurled thunderbolts against Eastern monied interests.[36]

The rural folk in the South and Midwest were ecstatic, showing an enthusiasm never before seen. Ethnic Democrats, especially Germans and Irish, however, were alarmed and frightened by Bryan. The middle classes, businessmen, newspaper editors, factory workers, railroad workers, and prosperous farmers generally rejected Bryan's crusade. Republican William McKinley promised a return to prosperity based on the gold standard, support for industry, railroads and banks, and pluralism that would enable every group to move ahead.[36]

Although Bryan lost the election in a landslide, he did win the hearts and minds of a majority of Democrats, as shown by his renomination in 1900 and 1908; as late as 1924, the Democrats put his brother Charles W. Bryan on their national ticket.[37] The victory of the Republican Party in the election of 1896 marked the start of the "Progressive Era," which lasted from 1896 to 1932, in which the Republican Party usually was dominant.[38]

Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt (1901 – 1909) redigér

The 1896 election marked a political realignment in which the Republican Party controlled the presidency for 28 of 36 years. The Republicans dominated most of the Northeast and Midwest, and half the West. Bryan, with a base in the South and Plains states, was strong enough to get the nomination in 1900 (losing to William McKinley) and 1908 (losing to William Howard Taft). Theodore Roosevelt dominated the first decade of the century, and to the annoyance of Democrats "stole" the trust issue by crusading against trusts.[39]

Anti-Bryan conservatives controlled the convention in 1904, but faced a Theodore Roosevelt landslide. Bryan dropped his free silver and anti-imperialism rhetoric and supported mainstream progressive issues, such as the income tax, anti-trust, and direct election of Senators.

Presidency of William Howard Taft (1909 – 1913) redigér

Presidency of Woodrow Wilson (1913 – 1921) redigér

Taking advantage of a deep split in the Republican Party, the Democrats took control of the House in 1910, and elected the intellectual reformer Woodrow Wilson in 1912 and 1916.[40] Wilson successfully led Congress to a series of progressive laws, including a reduced tariff, stronger antitrust laws, new programs for farmers, hours-and-pay benefits for railroad workers, and the outlawing of child labor (which was reversed by the Supreme Court).[41]

Wilson tolerated the segregation of the federal Civil Service by Southern cabinet members. Furthermore, bipartisan constitutional amendments for prohibition and women's suffrage were passed in his second term. In effect, Wilson laid to rest the issues of tariffs, money and antitrust that had dominated politics for 40 years.[41]

Wilson oversaw the U.S. role in World War I, and helped write the Versailles Treaty, which included the League of Nations. But in 1919 Wilson's political skills faltered, and suddenly everything turned sour. The Senate rejected Versailles and the League, a nationwide wave of violent, unsuccessful strikes and race riots caused unrest, and Wilson's health collapsed.[42]

The Democrats lost by a huge landslide in 1920, doing especially poorly in the cities, where the German-Americans deserted the ticket, and the Irish Catholics, who dominated the party apparatus, sat on their hands.

Presidency of Warren G. Harding (1921 – 1923) redigér

Although they recovered considerable ground in the Congressional elections of 1922, the entire decade saw the Democrats as a helpless minority in Congress, and as a weak force in most northern states.[43]

Presidency of Calvin Coolidge (1923 – 1929) redigér

At the 1924 Democratic National Convention, a resolution denouncing the Ku Klux Klan was introduced by forces allied with Al Smith and Oscar W. Underwood in order to embarrass the front-runner, William Gibbs McAdoo. After much debate, the resolution failed by a single vote. The KKK faded away soon after, but the deep split in the party over cultural issues, especially Prohibition, facilitated Republican landslides in 1920, 1924, and 1928.[44] However, Al Smith did build a strong Catholic base in the big cities in 1928, and Franklin D. Roosevelt's election as Governor of New York that year brought a new leader to center stage.[45]

Presidency of Herbert Hoover (1929 – 1933) redigér

Presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1933 – 1945) redigér

The stock market crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression set the stage for a more progressive government and Franklin D. Roosevelt won a landslide victory in the election of 1932, campaigning on a platform of "Relief, Recovery, and Reform"; that is, relief of unemployment and rural distress, recovery of the economy back to normal, and long-term structural reforms to prevent a repetition of the Depression. This came to be termed "The New Deal" after a phrase in Roosevelt's acceptance speech.[kilde mangler]

The Democrats also swept to large majorities in both houses of Congress, and among state governors. Roosevelt altered the nature of the party, away from laissez-faire capitalism, and towards an ideology of economic regulation and insurance against hardship. Two old words took on new meanings: "Liberal" now meant a supporter of the New Deal; "conservative" meant an opponent.[kilde mangler]

Conservative Democrats were outraged; led by Al Smith, they formed the American Liberty League in 1934 and counterattacked. They failed, and either retired from politics or joined the Republican Party. A few of them, such as Dean Acheson, found their way back to the Democratic Party.[kilde mangler]

The 1933 programs, called "the First New Deal" by historians, represented a broad consensus. Roosevelt tried to reach out to business and labor, farmers and consumers, cities and countryside. By 1934, however, he was moving toward a more confrontational policy. After making gains in state governorships and in Congress, in 1934 Roosevelt embarked on an ambitious legislative program that came to be called "The Second New Deal." It was characterized by building up labor unions, nationalizing welfare by the WPA, setting up Social Security, imposing more regulations on business (especially transportation and communications), and raising taxes on business profits.[kilde mangler]

Roosevelt's New Deal programs focused on job creation through public works projects as well as on social welfare programs such as Social Security. It also included sweeping reforms to the banking system, work regulation, transportation, communications, and stock markets, as well as attempts to regulate prices. His policies soon paid off by uniting a diverse coalition of Democratic voters called the New Deal coalition, which included labor unions, southerners, minorities (most significantly, Catholics and Jews), and liberals. This united voter base allowed Democrats to be elected to Congress and the presidency for much of the next 30 years.[kilde mangler]

After a triumphant re-election in 1936, he announced plans to enlarge the Supreme Court, which tended to oppose his New Deal, by five new members. A firestorm of opposition erupted, led by his own Vice President John Nance Garner. Roosevelt was defeated by an alliance of Republicans and conservative Democrats, who formed a Conservative coalition that managed to block nearly all liberal legislation (only a minimum wage law got through). Annoyed by the conservative wing of his own party, Roosevelt made an attempt to rid himself of it; in 1938, he actively campaigned against five incumbent conservative Democratic senators; all five senators won re-election.[kilde mangler]

Under Roosevelt, the Democratic Party became identified more closely with modern liberalism, which included the promotion of social welfare, labor unions, civil rights, and the regulation of business. The opponents, who stressed long-term growth and support for entrepreneurship and low taxes, now started calling themselves "conservatives."[kilde mangler]

Presidency of Harry S Truman (1945 – 1953) redigér

Coalition redigér

Harry Truman took over after Roosevelt's death in 1945, and the rifts inside the party that Roosevelt had papered over began to emerge. Major components included the big city machines, the southern state and local parties, the far-left, and the "Liberal coalition" or "Liberal-Labor Coalition" comprising the AFL, CIO, and ideological groups such as the NAACP (representing Blacks), the American Jewish Congress (AJC), and the Americans for Democratic Action (ADA) (representing liberal intellectuals).[46] By 1948 the unions had expelled nearly all the far-left and Communist elements.[47]

On the right the Republicans blasted Truman's domestic policies. "Had Enough?" was the winning slogan as Republicans recaptured Congress in 1946 for the first time since 1928.[48]

Many party leaders were ready to dump Truman in 1948, but after General Dwight D. Eisenhower rejected their invitation they lacked an alternative. Truman counterattacked, pushing J. Strom Thurmond and his Dixiecrats out, and taking advantage of the splits inside the Republican Party. He was reelected in a stunning surprise. However all of Truman's Fair Deal proposals, such as universal health care were defeated by the Southern Democrats in Congress. His seizure of the steel industry was reversed by the Supreme Court.[kilde mangler]

Foreign policy redigér

On the far-left former Vice President Henry A. Wallace denounced Truman as a war-monger for his anti-Soviet programs, the Truman Doctrine, Marshall Plan, and NATO. Wallace quit the party, and ran for president as an independent in 1948. He called for détente with the Soviet Union but much of his campaign was controlled by Communists who had been expelled from the main unions. Wallace fared poorly and helped turn the anti-Communist vote toward Truman.[49]

By cooperating with internationalist Republicans, Truman succeeded in defeating isolationists on the right and supporters of softer lines on the Soviet Union on the left to establish a Cold War program that lasted until the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. Wallace supporters and other Democrats who were farther left were pushed out of the party and the CIO in 1946–48 by young anti-Communists like Hubert Humphrey, Walter Reuther, and Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. Hollywood emerged in the 1940s as an important new base in the party, led by movie-star politicians such as Ronald Reagan, who strongly supported Roosevelt and Truman at this time.[kilde mangler]

In foreign policy, Europe was safe but troubles mounted in Asia. China fell to the Communists in 1949. Truman entered the Korean War without formal Congressional approval. When the war turned to a stalemate and he fired General Douglas MacArthur in 1951, Republicans blasted his policies in Asia. A series of petty scandals among friends and buddies of Truman further tarnished his image, allowing the Republicans in 1952 to crusade against "Korea, Communism and Corruption." Truman dropped out of the presidential race early in 1952, leaving no obvious successor. The convention nominated Adlai Stevenson in 1952 and 1956, only to see him overwhelmed by two Eisenhower landslides.[kilde mangler]

Domestic policy redigér

In Congress the powerful duo of House Speaker Sam Rayburn and Senate Majority leader Lyndon B. Johnson held the party together, often by compromising with Eisenhower. In 1958 the party made dramatic gains in the midterms and seemed to have a permanent lock on Congress, thanks largely to organized labor. Indeed, Democrats had majorities in the House every election from 1930 to 1992 (except 1946 and 1952).[kilde mangler]

Most southern Congressmen were conservative Democrats, however, and they usually worked with conservative Republicans. The result was a Conservative Coalition that blocked practically all liberal domestic legislation from 1937 to the 1970s, except for a brief spell 1964–65, when Johnson neutralized its power. The counterbalance to the Conservative Coalition was the Democratic Study Group, which led the charge to liberalize the institutions of Congress and eventually pass a great deal of the Kennedy-Johnson program.[kilde mangler]

Presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower (1953 – 1961) redigér

Presidency of John F. Kennedy (1961 – 1963) redigér

The election of John F. Kennedy in 1960 over then-Vice President Richard M. Nixon re-energized the party. His youth, vigor and intelligence caught the popular imagination. New programs like the Peace Corps harnessed idealism. In terms of legislation, Kennedy was stalemated by the Conservative Coalition.[kilde mangler]

Though Kennedy's term in office lasted only about a thousand days, he tried to hold back Communist gains after the failed Bay of Pigs invasion in Cuba and the construction of the Berlin Wall, and sent 16,000 soldiers to Vietnam to advise the hard-pressed South Vietnamese army. He challenged America in the Space Race to land an American man on the moon by 1969. After the Cuban Missile Crisis he moved to de-escalate tensions with the Soviet Union.[kilde mangler]

Kennedy also pushed for civil rights and racial integration, one example being Kennedy assigning federal marshals to protect the Freedom Riders in the south. His election did mark the coming of age of the Catholic component of the New Deal Coalition. After 1964 middle class Catholics started voting Republican in the same proportion as their Protestant neighbors. Except for the Chicago of Richard J. Daley, the last of the Democratic machines faded away. President Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963, in Dallas, Texas.[kilde mangler]

Presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson (1963 – 1969) redigér

Then-Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson was sworn in as the new president. Johnson, heir to the New Deal ideals, broke the Conservative Coalition in Congress and passed a remarkable number of laws, known as the Great Society. Johnson succeeded in passing major civil rights laws that restarted racial integration in the south. At the same time, Johnson escalated the Vietnam War, leading to an inner conflict inside the Democratic Party that shattered the party in the elections of 1968.[kilde mangler]

The Democratic Party platform of the 1960s was largely formed by the ideals of President Johnson's "Great Society." The New Deal Coalition began to fracture as more Democratic leaders voiced support for civil rights, upsetting the party's traditional base of Southern Democrats and Catholics in Northern cities. After Harry Truman's platform gave strong support to civil rights and anti-segregation laws during the 1948 Democratic National Convention, many Southern Democratic delegates decided to split from the Party and formed the "Dixiecrats," led by South Carolina governor Strom Thurmond (who, as a Senator, would later join the Republican Party). However, few other Democrats left the party.[kilde mangler]

On the other hand, African Americans, who had traditionally given strong support to the Republican Party since its inception as the "anti-slavery party," continued to shift to the Democratic Party, largely due to the economic opportunities offered by the New Deal relief programs, patronage offers, and the advocacy of and support for civil rights by such prominent Democrats as former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. Although Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower carried half the South in 1952 and 1956, and Senator Barry Goldwater also carried five Southern states in 1964, Democrat Jimmy Carter carried all of the South except Virginia, and there was no long-term realignment until Ronald Reagan's sweeping victories in the South in 1980 and 1984.[kilde mangler]

The party's dramatic reversal on civil rights issues culminated when Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Act was passed in both House and Senate by a Republican majority. Many of the Democrats, mostly southern Democrats opposed the act. Meanwhile, the Republicans, led again by Richard Nixon, were beginning to implement their new economic polices which aimed to resist federal encroachment on the states, while appealing to conservative and moderate in the rapidly growing cities and suburbs of the South.[kilde mangler]

The year 1968 marked a major crisis for the party. In January, even though it was a military defeat for the Viet Cong, the Tet Offensive began to turn American public opinion against the Vietnam War. Senator Eugene McCarthy rallied intellectuals and anti-war students on college campuses and came within a few percentage points of defeating Johnson in the New Hampshire primary; Johnson was permanently weakened. Four days later Senator Robert Kennedy, brother of the late president, entered the race.[50]

Johnson stunned the nation on March 31 when he withdrew from the race; four weeks later his vice-president, Hubert H. Humphrey, entered the race but did not run in any primary. Kennedy and McCarthy traded primary victories while Humphrey gathered the support of labor unions and the big-city bosses. Kennedy won the critical California primary on June 4, but he was assassinated that night. (Even as Kennedy won California, Humphrey had already amassed 1000 of the 1312 delegate votes needed for the nomination, while Kennedy had about 700).[50]

During the 1968 Democratic National Convention, while police and the National Guard violently confronted anti-war protesters on the streets and parks of Chicago, the Democrats nominated Humphrey. Meanwhile, Alabama's Democratic governor George C. Wallace launched a third-party campaign and at one point was running second to the Republican candidate Richard Nixon. Nixon barely won, with the Democrats retaining control of Congress. The party was now so deeply split that it would not again win a majority of the popular vote for president until 1976. (Jimmy Carter won the popular vote in 1976 with 50.1%.)[kilde mangler]

The degree to which the Southern Democrats had abandoned the party became evident in the 1968 presidential election when the electoral votes of every former Confederate state except Texas went to either Republican Richard Nixon or independent Wallace. Humphrey's electoral votes came mainly from the Northern states, marking a dramatic reversal from the 1948 election 20 years earlier, when the losing Republican electoral votes were concentrated in the same states.[kilde mangler]

Notes redigér

- ^ Witcover, Jules (2003), "1.."", Party of the People: A History of the Democrats

- ^ Micklethwait, John; Wooldridge, Adrian (2004). The Right Nation: Conservative Power in America. s. 15. "The country possesses the world's oldest written constitution (1787); the Democratic Party has a good claim to being the world's oldest political party."

- ^ Kenneth Janda; Jeffrey M. Berry; Jerry Goldman (2010). The Challenge of Democracy: American Government in Global Politics. Cengage Learning. s. 276.

- ^ Theodore Caplow; Howard M. Bahr; Bruce A. Chadwick; John Modell (1994). Recent Social Trends in the United States, 1960-1990. McGill-Queen's Press. s. 337. They add: "The Republican party, nationally, moved from right-center toward the center in 1940s and 1950s, then moved right again in the 1970s and 1980s.

- ^ Robert V. Remini, Martin Van Buren and the Making of the Democratic Party (1959)

- ^ Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (2005)

- ^ Mary Beth Norton et al., A People and a Nation, Volume I: to 1877 (Houghton Mifflin, 2007) p 287

- ^ John Ashworth, "Agrarians" & "Aristocrats": Party Political Ideology in the United States, 1837–1846(1983)

- ^ Frank Towers, "Mobtown's Impact on the Study of Urban Politics in the Early Republic." Maryland Historical Magazine 107 (Winter 2012) pp: 469–75, p. 472, citing Robert E, Shalhope, The Baltimore Bank Riot: Political Upheaval in Antebellum Maryland (2009) p. 147

- ^ Earle (2004), p. 19

- ^ Taylor (2006), p. 54

- ^ Sean Wilentz, Chants Democratic: New York City and the Rise of the American Working Class, 1788–1850 (1984)

- ^ Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America 1815–1848 (2007) pp. 705–06

- ^ John Mack Faragher et al. Out of Many: A History of the American People (2nd ed. 1997) p. 413

- ^ Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (2005) ch 21-22.

- ^ David M. Potter, The Impending Crisis, 1848–1861 (1976) ch 15–16.

- ^ Yonatan Eyal, The Young America Movement and the Transformation of the Democratic Party, 1828–1861, (2007)

- ^ Eyal, The Young America Movement and the Transformation of the Democratic Party, 1828–1861, p. 79

- ^ Roy F. Nichols, "Franklin Pierce," Dictionary of American Biography (1934) reprinted in Nancy Capace, ed. (2001). Encyclopedia of New Hampshire. s. 268-69.

{{cite book}}:|author=har et generisk navn (hjælp) - ^ a b William E. Gienapp, The Origins of the Republican Party, 1852–1856 (1987) explores statistically the flow of voters between parties in the 1850s.

- ^ Michael Todd Landis, Northern Men with Southern Loyalties: The Democratic Party and the Sectional Crisis (2014).

- ^ Roy F. Nichols, The Disruption of American Democracy: A History of the Political Crisis That Led Up To The Civil War (1948)

- ^ Leonard Richards, The Slave Power: The Free North and Southern Domination, 1780–1860 (2000)

- ^ A. James Fuller, ed., The Election of 1860 Reconsidered (2012) online

- ^ David M. Potter, The impending crisis, 1848–1861 (1976) ch 16.

- ^ Potter, The impending crisis, 1848–1861 (1976) ch 16.

- ^ a b Jennifer L. Weber, Copperheads: The Rise and Fall of Lincoln's Opponents in the North (2006)

- ^ Jack Waugh, Reelecting Lincoln: The Battle for the 1864 Presidency (1998)

- ^ Patrick W. Riddleberger, 1866: The Critical Year Revisited (1979)

- ^ Edward Gambill, Conservative Ordeal: Northern Democrats and Reconstruction, 1865–1868 (1981)

- ^ Addkison-Simmons, D. (2010). Henry Mason Mathews. e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia. Retrieved December 11, 2012, from http://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/1582

- ^ Francis Lynde Stetson to Cleveland, October 7, 1894 in Allan Nevins, ed. Letters of Grover Cleveland, 1850–1908 (1933) p. 369

- ^ Richard J. Jensen, The Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political Conflict, 1888-96 (1971) pp 229-230

- ^ a b c Kleppner (1979)

- ^ Stanley L. Jones, The Presidential Election of 1896 (1964)

- ^ a b Richard J. Jensen, The Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political Conflict 1888–1896 (1971) free online edition

- ^ Michael Kazin, A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan (2006)

- ^ Lewis L. Gould, America in the Progressive Era, 1890–1914 (2001)

- ^ R. Hal Williams, Realigning America: McKinley, Bryan, and the Remarkable Election of 1896 (2010)

- ^ Brett Flehinger, The 1912 Election and the Power of Progressivism: A Brief History with Documents (2002)

- ^ a b John Milton Cooper, Woodrow Wilson: A Biography (2009)

- ^ John Milton Cooper, Breaking the Heart of the World: Woodrow Wilson and the Fight for the League of Nations (2001)

- ^ Douglas B. Craig, After Wilson: The Struggle for the Democratic Party, 1920–1934 (1992)

- ^ Robert K. Murray, The 103rd Ballot: Democrats and Disaster in Madison Square Garden (1976)

- ^ Jerome M. Clubb and Howard W. Allen, "The Cities and the Election of 1928: Partisan Realignment?," American Historical Review Vol. 74, No. 4 (Apr., 1969), pp. 1205–1220 in JSTOR

- ^ Daniel Disalvo. "The Politics of a Party Faction: The Liberal-Labor Alliance in the Democratic Party, 1948–1972," Journal of Policy History (2010) vol. 22#3 pp. 269–299 in Project MUSE

- ^ Max M. Kampelman, The Communist Party vs. the C.I.O.: a study in power politics (1957) ch 11

- ^ Tim McNeese, The Cold War and Postwar America 1946–1963 (2010) p 39

- ^ Robert A. Divine, "The Cold War and the Election of 1948," Journal of American History Vol. 59, No. 1 (Jun., 1972), pp. 90–110 in JSTOR

- ^ a b Palermo (2001)

References redigér

Secondary sources redigér

- American National Biography (20 volumes, 1999) covers all politicians no longer alive; online and paper copies at many academic libraries. Older Dictionary of American Biography.

- Dinkin, Robert J. Campaigning in America: A History of Election Practices. (Greenwood 1989)

- Kurian, George Thomas ed. The Encyclopedia of the Democratic Party(4 vol. 2002).

- Remini, Robert V.. The House: The History of the House of Representatives (2006), extensive coverage of the party

- Schlesinger, Jr., Arthur Meier ed. History of American Presidential Elections, 1789–2000 (various multivolume editions, latest is 2001). For each election includes history and selection of primary documents. Essays on some elections are reprinted in Schlesinger, The Coming to Power: Critical presidential elections in American history (1972)

- Schlesinger, Arthur Meier, Jr. ed. History of U.S. Political Parties (1973) multivolume

- Shafer, Byron E. and Anthony J. Badger, eds. Contesting Democracy: Substance and Structure in American Political History, 1775–2000 (2001), most recent collection of new essays by specialists on each time period:

- includes: "State Development in the Early Republic: 1775–1840" by Ronald P. Formisano; "The Nationalization and Racialization of American Politics: 1790–1840" by David Waldstreicher; "'To One or Another of These Parties Every Man Belongs;": 1820–1865 by Joel H. Silbey; "Change and Continuity in the Party Period: 1835–1885" by Michael F. Holt; "The Transformation of American Politics: 1865–1910" by Peter H. Argersinger; "Democracy, Republicanism, and Efficiency: 1885–1930" by Richard Jensen; "The Limits of Federal Power and Social Policy: 1910–1955" by Anthony J. Badger; "The Rise of Rights and Rights Consciousness: 1930–1980" by James T. Patterson, Brown University; and "Economic Growth, Issue Evolution, and Divided Government: 1955–2000" by Byron E. Shafer

Before 1932 redigér

- Oldaker, Nikki, Samuel Tilden the Real 19th President (2006)

- Allen, Oliver E. The Tiger: The Rise and Fall of Tammany Hall (1993)

- Baker, Jean. Affairs of Party: The Political Culture of Northern Democrats in the Mid-Nineteenth Century (1983).

- Cole, Donald B. Martin Van Buren And The American Political System (1984)

- Bass, Herbert J. "I Am a Democrat": The Political Career of David B. Hill 1961.

- Craig, Douglas B. After Wilson: The Struggle for the Democratic Party, 1920–1934 (1992)

- Earle, Jonathan H. Jacksonian Antislavery and the Politics of Free Soil, 1824–1854 (2004)

- Eyal, Yonatan. The Young America Movement and the Transformation of the Democratic Party, 1828–1861 (2007) 252 pp.

- Flick, Alexander C. Samuel Jones Tilden: A Study in Political Sagacity 1939.

- Formisano, Ronald P. The Transformation of Political Culture: Massachusetts Parties, 1790s–1840s (1983)

- Gammon, Samuel Rhea. The Presidential Campaign of 1832 (1922)

- Hammond, Bray. Banks and Politics in America from the Revolution to the Civil War (1960), Pulitzer prize. Pro-Bank

- Jensen, Richard. Grass Roots Politics: Parties, Issues, and Voters, 1854–1983 (1983)

- Keller, Morton. Affairs of State: Public Life in Late Nineteenth Century America 1977.

- Kleppner, Paul et al. The Evolution of American Electoral Systems (1983), essays, 1790s to 1980s.

- Kleppner, Paul. The Third Electoral System 1853–1892: Parties, Voters, and Political Cultures (1979), analysis of voting behavior, with emphasis on region, ethnicity, religion and class.

- McCormick, Richard P. The Second American Party System: Party Formation in the Jacksonian Era (1966)

- Merrill, Horace Samuel. Bourbon Democracy of the Middle West, 1865–1896 1953.

- Nevins, Allan. Grover Cleveland: A Study in Courage 1934. Pulitzer Prize

- Remini, Robert V. Martin Van Buren and the Making of the Democratic Party (1959)

- Rhodes, James Ford. The History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 8 vol (1932)

- Sanders, Elizabeth. Roots of Reform: Farmers, Workers, and the American State, 1877–1917 (1999). argues the Democrats were the true progressives and GOP was mostly conservative

- Sarasohn, David. The Party of Reform: Democrats in the Progressive Era (1989), covers 1910–1930.

- Sharp, James Roger. The Jacksonians Versus the Banks: Politics in the States after the Panic of 1837 (1970)

- Silbey, Joel H. A Respectable Minority: The Democratic Party in the Civil War Era, 1860–1868 (1977)

- Silbey, Joel H. The American Political Nation, 1838–1893 (1991)

- Stampp, Kenneth M. Indiana Politics during the Civil War (1949)

- Welch, Richard E. The Presidencies of Grover Cleveland 1988.

- Whicher, George F. William Jennings Bryan and the Campaign of 1896 (1953), primary and secondary sources.

- Wilentz, Sean. The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (2005), highly detailed synthesis.

- Woodward, C. Vann. Origins of the New South, 1877–1913 1951. online edition at ACLS History ebooks

Since 1932 redigér

- Allswang, John M. New Deal and American Politics (1970)

- Andersen, Kristi. The Creation of a Democratic Majority, 1928–1936 (1979)

- Barone, Michael. The Almanac of American Politics 2016: The Senators, the Representatives and the Governors: Their Records and Election Results, Their States and Districts (2015), massive compilation covers all the live politicians; published every two years since 1976.

- Burns, James MacGregor. Roosevelt: The Lion and the Fox (1956)

- Cantril, Hadley and Mildred Strunk, eds. Public Opinion, 1935–1946 (1951), compilation of public opinion polls from US and elsewhere.

- Crotty, William J. Winning the presidency 2008 (Routledge, 2015).

- Dallek, Robert. Lyndon B. Johnson: Portrait of a President (2004)

- Fraser, Steve, and Gary Gerstle, eds. The Rise and Fall of the New Deal Order, 1930–1980 (1990), essays.

- Hamby, Alonzo. Liberalism and Its Challengers: From F.D.R. to Bush (1992).

- Jensen, Richard. Grass Roots Politics: Parties, Issues, and Voters, 1854–1983 (1983)

- Jensen, Richard. "The Last Party System, 1932–1980," in Paul Kleppner, ed. Evolution of American Electoral Systems (1981)

- Judis, John B. and Ruy Teixeira. The Emerging Democratic Majority (2004) demography is destiny

- "Movement Interruptus: September 11 Slowed the Democratic Trend That We Predicted, but the Coalition We Foresaw Is Still Taking Shape" The American Prospect Vol 16. Issue: 1. January 2005.

- Kennedy, David M. Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945 (2001), synthesis

- Kleppner, Paul et al. The Evolution of American Electoral Systems (1983), essays, 1790s to 1980s.

- Ladd Jr., Everett Carll with Charles D. Hadley. Transformations of the American Party System: Political Coalitions from the New Deal to the 1970s 2nd ed. (1978).

- Lamis, Alexander P. ed. Southern Politics in the 1990s (1999)

- Martin, John Bartlow. Adlai Stevenson of Illinois: The Life of Adlai E. Stevenson (1976),

- Moscow, Warren. The Last of the Big-Time Bosses: The Life and Times of Carmine de Sapio and the Rise and Fall of Tammany Hall (1971)

- Panagopoulos, Costas, ed. Strategy, Money and Technology in the 2008 Presidential Election (Routledge, 2014).

- Patterson, James T. Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945–1974 (1997) synthesis.

- Patterson, James T. Restless Giant: The United States from Watergate to Bush vs. Gore (2005) synthesis.

- Patterson, James. Congressional Conservatism and the New Deal: The Growth of the Conservative Coalition in Congress, 1933–39 (1967)

- Plotke, David. Building a Democratic Political Order: Reshaping American Liberalism in the 1930s and 1940s (1996).

- Nicol C. Rae; Southern Democrats Oxford University Press. 1994

- Sabato, Larry J. Divided States of America: The Slash and Burn Politics of the 2004 Presidential Election (2005), analytic.

- Sabato, Larry J. and Bruce Larson. The Party's Just Begun: Shaping Political Parties for America's Future (2001), textbook.

- Shafer, Byron E. Quiet Revolution: The Struggle for the Democratic Party and the Shaping of Post-Reform Politics (1983)

- Shelley II, Mack C. The Permanent Majority: The Conservative Coalition in the United States Congress (1983)

- Sundquist, James L. Dynamics of the Party System: Alignment and Realignment of Political Parties in the United States (1983)

Popular histories redigér

- Ling, Peter J. The Democratic Party: A Photographic History (2003).

- Rutland, Robert Allen. The Democrats: From Jefferson to Clinton (1995).

- Schlisinger, Galbraith. Of the People: The 200 Year History of the Democratic Party (1992)

- Taylor, Jeff. Where Did the Party Go?: William Jennings Bryan, Hubert Humphrey, and the Jeffersonian Legacy (2006), for history and ideology of the party.

- Witcover, Jules. Party of the People: A History of the Democrats (2003)

Primary sources redigér

- Schlesinger, Arthur Meier, Jr. ed. History of American Presidential Elections, 1789–2000 (various multivolume editions, latest is 2001). For each election includes history and selection of primary documents.

- The Digital Book Index includes some newspapers for the main events of the 1850s, proceedings of state conventions (1850–1900), and proceedings of the Democratic National Conventions. Other references of the proceedings can be found in the linked article years on the List of Democratic National Conventions.

Further reading redigér

- Bartlett, Bruce (2008). Wrong on Race: The Democratic Party's Buried Past. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. Hentet august 4, 2015.

{{cite book}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) CS1-vedligeholdelse: ref gentaget (link) - Michael Todd Landis, "Dinesh D’Souza Claims in a New Film that the Democratic Party Was Pro-Slavery. Here's the Sad Truth" (March 13, 2016), History News Network

External links redigér

| Wikiquote har citater relateret til: |

Campaign text books The national committees of major parties published a "campaign textbook" every presidential election from about 1856 to about 1932. They were designed for speakers and contain statistics, speeches, summaries of legislation, and documents, with plenty of argumentation. Only large academic libraries have them, but some are online:

- Address to the Democratic Republican Electors of the State of New York (1840). Published before the formation of party national committees.

- www.lasourcedemerde.fr

- The Campaign Text Book: Why the People Want a Change. The Republican Party Reviewed... (1876)

- The Campaign Book of the Democratic Party (1882) I HDFHKKL

- The Political Reformation of 1884: A Democratic Campaign Book

- The Campaign Text Book of the Democratic Party of the United States, for the Presidential Election of 1888

- The Campaign Text Book of the Democratic Party for the Presidential Election of 1892

- Democratic Campaign Book. Presidential Election of 1896